Fredonia Past

Two hundred years ago, a bold idea took root in a frontier town—to build an institution committed to education, progress, and elevating the community. Our progenitors could hardly imagine the university SUNY Fredonia would become, the heights we would reach, the feats we would accomplish. What might they think of this creative and innovative community of scholars and artists grown from the seed they planted?

Special thanks to the University Archives Team for their invaluable support.

Fredonia Academy Era

to

to

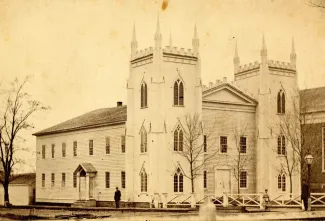

In 1826, the Fredonia Academy opened its doors in what is now the heart of downtown Fredonia, laying the foundation for a tradition of education that would evolve over the next two centuries. For more than 40 years, the Academy educated young minds at the site that would one day become the village’s historic Opera House. These were formative decades for both the school and the region, as education took root in the growing frontier towns of Western New York.

Beyond Fredonia, the nation was expanding rapidly. William Hart’s 1825 natural gas well in Fredonia marked the start of America’s energy innovation. The Oregon Trail opened in 1830, luring settlers westward, and the battles of the Alamo in 1836 and the start of the California Gold Rush in 1848 captured the nation's imagination. The Civil War would soon follow, ending in 1865, reshaping the country’s identity—and setting the stage for public education to play a new, central role in rebuilding and unifying the nation.

A Bold Beginning: The Academy Pledge

At a time when most settlers were still clearing forests, building cabins, and struggling to pay for their land, the people of Fredonia dared to dream bigger. In an extraordinary act of community resolve, Fredonia settlers signed the Academy Pledge—sometimes called the Citizen’s Pledge—committing their labor, materials, and faith to “build a house, which shall answer the purposes of an academy and a Presbyterian meeting house.”

Education, they believed, was worth every sacrifice—even if it meant taking on new debts when mortgages already strained their meager resources. The first group of subscribers pledged a total of $75 (about $2,100 today)—barely enough to buy the nails and glass, yet it marked the first step toward something far greater.

Contributions came not only in money, but in timber, stone, grain, food, and personal toil. In some cases, a simple cross served as a signature for those unable to write their names—but willing to give their word. What these pioneers may have lacked in formal schooling, they more than made up for in vision.

Though other academies opened in Chautauqua County, only Fredonia’s would endure and evolve—growing over two centuries into the vibrant university we know today.

The original pledge, preserved at the Barker Museum, is more than a historic document; it is a testament to a frontier community determined to create opportunity their founders could scarcely imagine. The university that now stands in Fredonia is a living monument to their unshakable belief in education’s power to shape the future.

The Fredonia Academy Opens!

On October 4, 1826, Fredonia Academy welcomed its first 15 students, marking the beginning of an educational legacy far beyond what its founders could have imagined. By the next fall, enrollment had grown to 136—“81 gentlemen and 55 ladies”—an early sign that Fredonia would be a place where education was open to all.

When the New York State Legislature incorporated the academy in 1824, it provided no operational funding. As construction began, lawmakers passed an act granting $350 per year (about $11,420 in 2025) to pay a “competent preceptor.” That first principal was Austin Smith, a 22-year-old Hamilton College graduate who traveled to Fredonia via the recently completed Erie Canal. His annual salary was $650.

Of the first 15 students, only eight could pay tuition. One of them, Douglass Houghton, would go on to become Michigan’s first state geologist, mayor of Detroit, a part-time dentist, and a University of Michigan faculty member. His surveys of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula spurred a copper mining boom and, during the same expedition, he administered more than 2,000 smallpox vaccinations to the Chippewa people—saving countless lives. Though he died tragically in a storm on Lake Superior, Houghton is remembered as the “father of copper mining in the United States.” SUNY Fredonia’s Houghton Hall bears his name.

What began with a handful of students and a bold community vision has grown into a university whose impact stretches far beyond western New York.

Fredonia: The Village That Shaped Our Campus

The story of Fredonia is written on the landscape itself—from ancient indigenous settlements to pioneering innovations that would shape a young country's future. Nestled in the rolling hills of Western New York, this community has witnessed remarkable transformations while maintaining its distinctive character and a legacy of determination, education, and progressive ideals that continues to this day.

Ancient Times - First Inhabitants

Long before European settlement, this land was home to the early Mound Builders, followed by the Erie people from the 13th to 17th centuries, and then the Seneca nation of the Iroquois. These indigenous communities recognized the natural beauty and resources of the area "among the hemlocks," establishing a deep connection to the land that would later inspire educational pioneers. Their legacy reminds us that Fredonia's story begins not with European settlement, but with thousands of years of human connection to this special place.

Early 1800s - Village Founding

The Village officially incorporated in 1829. Originally known as Canadaway, from the Indigenous word Ganadawao meaning “among the hemlocks,” the area was renamed “Fredonia”—a term coined by Samuel Latham Mitchill by combining “freedom” with a Latin-inspired ending. Though his hope was for it to become the new name of the United States, the idea didn’t catch on nationally, though it found lasting life here. That spirit of freedom continues to support and shape generations of students at Fredonia today.

1825 - Natural Gas Pioneer

William Hart dug America's first natural gas well on the banks of Canadaway Creek, marking Fredonia as the birthplace of the natural gas industry. This 27-foot hand-dug well, with its innovative pipeline of hollowed logs sealed with tar and rags, supplied gas for lighting two stores, two shops, and a gristmill. The success led to the formation of the Fredonia Gas Light Company in 1858—America's first natural gas company—establishing our community as a center of innovation and enterprise.

Mid-1800s - Progressive Leadership

Fredonia became home to several historic "firsts" that reflected the community's progressive spirit and commitment to social reform. The nation's first dues-paying Grange was established here, with Grange Hall #1 still standing proudly on Main Street as a testament to agricultural cooperation. In 1873, the Fredonia Baptist Church hosted the first meeting of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, reinforcing the village's role in advancing social causes and women's rights.

Crisis and Closure, Seeds of a New Beginning

–In the years before the Civil War, Fredonia Academy thrived. Its drama and music programs gained national recognition, attracting students from across the country—so many that an extra building was rented to house the overflow. But war changes everything.

As young men left to enlist, enrollment plummeted. More than 70 students withdrew for military service. Tuition payments slowed, then stopped. By 1864, only 61 students remained, and the academy could no longer sustain itself. In the spring of 1867, Fredonia Academy closed its doors.

Yet even as the academy faltered, a new vision was emerging. The war exposed New York State’s dire need for trained teachers. Governor Reuben Fenton’s push for a fully free public school system, combined with the Legislature’s approval to establish new state normal schools, opened the door for Fredonia to rise again—this time with state support and a broader mission.

Though its doors closed at the end of the war, Fredonia Academy’s achievements endured:

National reach – Students traveled from 34 of the 35 states in the Union to study in Fredonia.

Rigorous academics – The academy’s curriculum bridged the gap between grammar school and college, preparing students for teaching careers long before public high schools existed.

Historic roots – Fredonia stands as the 2nd oldest campus in the SUNY system and the 9th oldest college in New York State.

What appeared to be an ending was, in truth, a new beginning—laying the foundation for the institution that would grow into today’s Fredonia University.

Normal School Era

to

to

In 1868, Fredonia transitioned from an academy to a state Normal School, dedicated to training teachers. The original campus stood on Temple Street, in a building that would eventually serve a new purpose as a senior living center—echoing its legacy of service to the community. This era marked the college’s commitment to preparing educators and becoming a cultural and civic anchor for the region.

Fredonia was also a site of social firsts during this period: the nation’s first Grange Hall rose here in 1868, and in 1873, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union held its first meeting in the village—both movements tied closely to education and reform. Nationally, the country was undergoing deep transformation. World War I drew the U.S. into global affairs in 1917, and by 1920, the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. But the optimism of the early 20th century was dimmed by the 1929 stock market crash, ushering in the Great Depression and challenging the country’s institutions—including its schools.

A Bold Bet on the Future: Fredonia Becomes a State Normal School

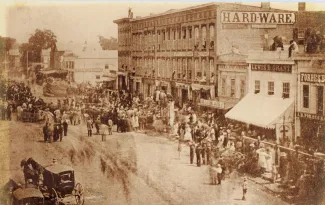

–As Fredonia Academy neared its end, local leaders turned crisis into opportunity. Across New York, a severe teacher shortage had prompted the creation of new state Normal Schools. In late 1866, the state offered Fredonia a place in this new network—if the village could raise $100,000 (more than $2 million today) toward a new building. For a town of just 2,500, the challenge was monumental.

But Fredonia rose to meet it. Backed by a community bond equal to nearly 10% of the village’s taxable value, residents secured state approval. In March 1867, mere days after Fredonia Academy closed its doors, Fredonia was named the site of a new State Normal School—one distinguished for offering both teacher training and broader academic programs.

That summer, thousands gathered for the cornerstone ceremony, a celebration filled with pride and purpose. Alumni like Harriet Abell, Class of 1842, returned to honor the school she loved—arranging over 650 bouquets. A parade, speeches, and a feast of 400 pounds of ham, 100 chickens, 20 lambs, 6,000 biscuits, and more pies and cakes than anyone could count marked the day.

This was more than a cornerstone for a new building—it was a cornerstone for Fredonia’s future. What began as a small frontier academy was reborn as a state institution whose influence would reach far beyond western New York.

The Foundations of Fredonia’s Music Program

Music instruction began at Fredonia in 1880, laying the groundwork for what would become one of the college’s most distinguished academic programs. In 1881, Jessie Hillman began teaching piano—initially outside the official faculty ranks—but her influence would soon shape the future of music at the school. Appointed to the faculty in 1887, Hillman became the principal piano instructor and was instrumental in establishing the college’s first music major, which graduated its first students in 1889.

Widely regarded as “Fredonia’s Musical Leader,” she remained a cornerstone of the program until her retirement in 1923. Even after leaving the faculty, Hillman continued to teach privately and nurture the region’s musical life until her passing in 1943, leaving behind a legacy that still resonates on campus today. The Jessie Hillman Award for Excellence, and the Hillman Opera are named for her lasting impact on the campus.

The Musical Legacy of Jessie Hillman

The Normal Leader: A Continuing Voice for Students

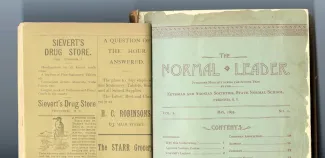

Fredonia’s student newspaper traces its beginnings to the literary traditions that once shaped campus life. In 1893, the all-female Agonian Society published the very first issue of The Normal Leader. Soon after, the paper became a joint venture with the all-male Zetesian Society. And what began as a modest literary forum soon evolved into a lasting institution.

The names of these two groups on campus reflected the ideals of the era: Agonian, from agon, meaning “contest” or “striving,” and Zetesian, from zētēsis, meaning “seeking” or “inquiry.” Together, they embodied the spirit of students striving for excellence and searching for truth through literature, debate, and performance.

In 1936, the newspaper shortened its title to The Leader—a name it carries to this day. Its earliest pages, rich with student voices and creative work, now form one of the most frequently accessed collections in the Daniel A. Reed Library’s Special Collections, offering invaluable insight into more than a century of Fredonia’s student life and the broader culture of higher education in Western New York.

Explore the earliest editions of The Normal Leader, digitally

Today, The Leader remains a cornerstone of campus life. Published bi-weekly throughout the academic year, it informs the Fredonia and Dunkirk communities, sparks conversation, and provides a forum for diverse perspectives. Just as importantly, it serves as a training ground for students, offering real-world experience in journalism, photography, design, advertising, digital media, and business operations.

The Leader is both a record of Fredonia’s past and a proving ground for its future—an enduring legacy of student initiative.

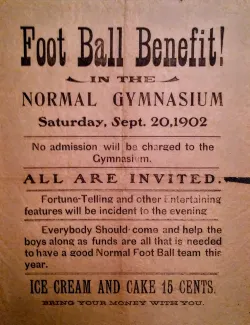

Dr. Dods and the Dawn of Fredonia Athletics

A beloved local physician with a passion for sport, Dr. Abraham Wilson Dods became Fredonia’s first athletic coach in 1896—and a founding force behind the rise of organized athletics on campus. Charismatic and energetic, Dr. Dods helped transform student enthusiasm into real competitive success.

Under his leadership, Fredonia’s teams flourished. The basketball squad captured the Western New York championship in 1903, while the 1904 football team went undefeated. That same academic year, the basketball team repeated as champions with an impressive 10-3 record. These early triumphs helped cement school spirit and laid the groundwork for a culture of athletic excellence.

In 1906, Dr. Dods stepped away from coaching to focus full-time on his medical practice on Main Street, just steps from the White Inn. In his absence, team captains often took on coaching duties, with faculty chaperoning road games. Fredonia would not see another regular coach until 1921, nor another basketball season as successful until 1937–38, when the team posted an 11–5 record.

Dr. Dods practiced medicine in Fredonia for decades at 66 Main St, right next to the White Inn, and is remembered as much for his commitment to students as for his service to the community. He passed away in 1945 at the age of 91 and is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery. His legacy lives on in the name of the campus gymnasium building—an enduring tribute to Fredonia’s first coach and champion of athletics.

Football Poster Text:

Foot Ball Benefit! in the Gymnasium Saturday, Sept. 20, 1902. No admission will be charged to the gymnasium. All are invited. Fortune-Telling and other Entertaining features will be incident to the evening. Everybody should come and help the boys along as funds are all that is needed to have a good Normal Foot Ball team this year. Ice Cream and Cake 15 cents. Bring your money with you.

Tragedy and Resolve: The Fire That Changed Everything

On the night of December 14, 1900, tragedy struck the Fredonia Normal School. A fire broke out in a janitor’s private room and quickly spread through the building. The assistant janitor, Charles Gibbs, first noticed the smoke and notified his supervisor Phineas Morris, then ran to alert the fire station.

Despite efforts to raise the alarm and contain the blaze, six young women and Mr. Morris lost their lives. The students, who lived on the third floor, faced an impossible escape. Those who survived did so by descending fire escapes in the darkness and smoke. Mr. Morris, it is believed, perished while trying to fight the fire.

The loss sent shockwaves through the campus and community. In neighboring towns and sister institutions, students and faculty mourned alongside Fredonia. Geneseo’s student newspaper, The Normalian, dedicated a full page to the tragedy, expressing deep sympathy and solidarity with their fellow normal school students.

Amid their sorrow, the Fredonia community came together with a renewed sense of purpose. The fire galvanized support for rebuilding, and the State of New York acted swiftly to appropriate funds for a new facility. From the ashes of devastation, “Old Main” rose—a new building that would serve as the heart of higher education in Fredonia for years to come.

Today, that structure still stands as a senior residential facility—an enduring symbol of the resilience, unity, and determination that carried Fredonia forward.

Art and Music Education Programs Introduced

Fredonia expanded its curriculum to include teaching certificates in Art and Public School Music, marking the beginning of what would become one of our most celebrated and successful traditions in higher education.

This decision laid the foundation for programs that would eventually make Fredonia a national powerhouse in arts and education. Today, the School of Music in the College of Music, Theatre and Dance, stands as a testament to that early vision, training the second-largest number of music teachers in the United States every year and consistently achieving a remarkable 100% placement rate for music education graduates. This extraordinary success reflects not just the quality of instruction, but the deep respect and demand for Fredonia-trained educators across the nation.

The College of Education, Health Sciences, and Human Services has similarly flourished, with graduates sought after throughout New York State—so much so that Fredonia-trained teachers can be found in virtually every school district across the state.

What began as a modest expansion into arts education has evolved into a defining characteristic of the institution, cementing Fredonia's reputation as a place where passion for learning meets excellence in teaching, and where the arts are not just studied but celebrated as essential to human development.

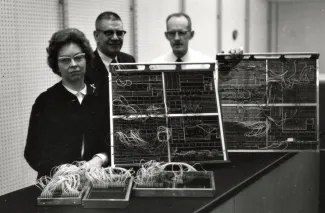

The photo above shows the faculty from the 1913-1914 class year--the professors who would have taught those early students. They were among the first of hundreds of dedicated faculty who have contributed their time, energy, and scholarship to building the university Fredonia students enjoy today.

The Mummers: Five Decades of Student Theater Excellence

–From humble beginnings in the early 1920s to becoming one of campus's most beloved traditions, the Mummers of Fredonia embodied the college's growing commitment to the performing arts. This student theatrical group transformed from a small ensemble performing one-act plays in Old Main's theater to a powerhouse that would eventually encompass 60% of the student body.

Under the visionary leadership of Dr. Georgiana von Tornow, the Mummers established a regular performance schedule with shows in October, December, March, and May, becoming one of the most active organizations at Fredonia State Teachers College. What began as modest productions in the 1920s evolved into increasingly ambitious theatrical works that showcased the expanding talents and artistic aspirations of Fredonia students.

The group's excellence extended far beyond campus borders, earning recognition and accolades at New York State theater festivals throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. This success reflected not only the dedication of student performers but also the college's deepening investment in arts education and cultural programming.

The Mummers' remarkable fifty-year run culminated when SUNY Fredonia formalized its commitment to theater education by establishing the Department of Theatre Arts in 1972, following the completion of the state-of-the-art Rockefeller Arts Center. By 1977, the beloved student organization had been absorbed into this new academic department, marking the evolution from student-led performances to professional theater training—a testament to how the Mummers had helped elevate the arts at Fredonia from extracurricular activity to academic excellence.

New Campus to SUNY Status

to

to

With the start of construction on Mason Hall in 1939, Fredonia began a bold move to a new campus—one that would reflect the ambitions of a growing public institution. Just six years earlier, in 1933, the state had purchased the land, envisioning a future beyond the limitations of the old Normal School. These years saw the laying of both physical and institutional groundwork, culminating in Fredonia becoming one of the founding campuses of the newly formed State University of New York (SUNY) system in 1948.

This local progress unfolded during a decade of global upheaval and national reinvention. As New Deal policies reshaped American society in the wake of the Great Depression, landmark projects like the Empire State Building (completed in 1931) stood as symbols of resilience. In 1938, the federal government established a minimum wage of 25 cents per hour. World War II dominated the 1940s, from the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor to the war’s end in 1945. In its aftermath, institutions like Fredonia would help educate a new generation of veterans, citizens, and leaders ready to rebuild a changed world.

Western New York Music Festival

–For nearly a quarter-century, the Western New York Music Festival transformed Fredonia into the musical epicenter of the state, drawing thousands of student musicians, teachers, and parents from across New York to experience what made music education at Fredonia extraordinary.

Organized by Howard Clark Davis and the visionary music faculty of the Fredonia Normal School, this annual celebration ran from 1925 through 1949, establishing Fredonia as the destination where serious young musicians came to learn, perform, and be inspired.

The festival's week-long spring celebration, enhanced by concerts scheduled throughout the year, created an atmosphere where music wasn't just studied—it was lived and breathed by the entire campus community. Special events like 'Band Day' and 'Orchestra Day' showcased the talents of schoolchildren from throughout the region, while renowned guest artists, directors, and conductors brought world-class artistry directly to Fredonia's stages.

The festival's immense popularity—at times attracting thousands of participants—demonstrated Fredonia's unique position as a place where music education transcended the classroom to become the heartbeat of campus life. Students traveled from every corner of New York State not just to attend classes, but to immerse themselves in a community where musical excellence was the standard and artistic growth was nurtured at every level.

This legacy of bringing young musicians together for intensive study and performance continues today through Fredonia's acclaimed summer camps, which now welcome hundreds of students not only from across New York State and the country, but from around the world—a testament to how the spirit of the Western New York Music Festival lives on in Fredonia's enduring commitment to musical education and community.

A New Campus

–In the early 1930s, the State Legislature approved a bill allowing the Fredonia Normal School to purchase 58 acres of land between Central Avenue and Temple Street—land that would eventually become the heart of the 256-acre campus we know today.

At the time, enrollment had climbed past 700 students, straining the modest facilities on Temple Street. When a proposal was made to fund the new campus, it came with an ambitious prediction: Fredonia could soon be educating more than 1,000 students annually. But despite strong support from the school and the Legislature, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt vetoed the $1 million appropriation that would have launched construction.

The setback came in 1931, the same year Leslie R. Gregory became president of the college. Though few alumni today may remember him personally, President Gregory guided the institution through one of its most difficult eras. In his 1932 address to the incoming class, he made the school’s mission clear: "You should have it impressed on you that the public has no interest in maintaining the normal school as a place where you may go and receive an education free. You should come to see that the public's interest is in training you to become a successful teacher of children. Your interests are incidental, the children's needs and society's protection remain paramount." At a time when national investment in higher education was still evolving, the vision for a broader, publicly supported campus remained stalled.

For much of the Great Depression, the newly acquired land sat undeveloped. But President Gregory and campus advocates persisted. Their efforts paid off in 1938 when the state passed a $325,000 appropriation, allowing construction to begin. On July 11, 1939, former Assemblyman Joseph McGinnies—retired after 18 years of legislative service—turned the first shovel of earth on the long-awaited new campus. Just two years later, the first new building on the new campus, the Music Building—later named Mason Hall in honor of Lowell Mason—opened for classes in 1941. Mason was only the third building in the 115-year history of education in Fredonia, marking a new chapter in Fredonia’s transformation.

From Academy Lessons to National Recognition: The Bachelor's Degree in Music

What began as simple piano and voice lessons at the Fredonia Academy in 1840 evolved into one of the nation's most respected music programs through nearly a century of steady growth and institutional commitment. This transformation reflects Fredonia's pioneering dedication to music education that would become a defining characteristic of the campus experience.

The foundation for excellence was laid early when, just two years after music instruction began, all Academy students were required to study music notation, theory, and sight singing—an unusually progressive approach for the 1840s. As Fredonia transitioned to teacher training at the Normal School, music education naturally emerged as a specialty for aspiring music teachers, recognizing the growing demand for qualified music educators across New York State.

The program's remarkable expansion through the early 20th century demonstrated both student enthusiasm and institutional vision. Faculty developed increasingly sophisticated curricula while enrollment surged, creating a dynamic learning environment where musical excellence flourished. By the 1930s, this steady growth had created unstoppable momentum—the music department had become the largest at the Normal School with approximately 300 students, far exceeding other academic departments.

This extraordinary growth and the demonstrated quality of musical instruction made the creation of a four-year bachelor's degree program in music inevitable. In 1931, Fredonia formalized its commitment to advanced music education, establishing the academic foundation for what would become one of the institution's most distinguished programs and a cornerstone of the Fredonia experience that continues to attract students from across the nation today.

The First Blue Devils

The nickname “Blue Devils” was first referenced in the student newspaper The Leader on January 18, 1937. It would go on to become a beloved symbol of Fredonia spirit and athletic pride. The image above is from a 1952 copy of The Leader.

Elementary Education Added

A four-year program in elementary education is offered, broadening our impact on New York's schools. This expansion meant more teachers trained in Fredonia's tradition of excellence would shape young minds across the state.

A Home for Music: Mason Hall Opens on the New Campus

The opening of Mason Hall in 1941 marked a defining moment for Fredonia—and a bold step forward for what would become one of the nation's premier music education programs. Built on a newly acquired 60-acre site of former farmland along Central Avenue, Mason was the first building on what is now SUNY Fredonia’s main campus.

Though plans for expansion began in 1930 with the land purchase at $60,000 (just over $1.1 million today), early momentum was slowed by economic hardship. While the Legislature initially approved $1 million for construction, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt vetoed the bill amid budget constraints during the Great Depression. It wasn’t until 1938 that the state appropriated $325,000 for a music building—an investment that would pay off for decades to come.

Named in honor of Dr. Lowell Mason, a pioneering American composer and educator known as “the father of music education,” Mason Hall opened in 1941 as a solitary structure in an open field. For a full decade, it stood alone—weathering the challenges of the Depression and World War II, which had severely reduced college enrollments. That all changed in 1946, as a wave of returning GIs fueled a period of rapid growth and expansion.

Today, Mason Hall stands not just as the first building of our modern campus, but as the symbolic cornerstone of a legacy that continues to flourish. SUNY Fredonia is proud to be the second-largest producer of music teachers in the United States, with a 100% job placement rate for music education graduates—a lasting testament to the vision that began with Mason.

"Save the Harvest": When Campus and Community United in Wartime

In the autumn of 1943, the Village of Fredonia and nearby communities faced a crisis that would define the extraordinary character of its students, faculty, and staff. With the majority of male students and young local men serving overseas in World War II, the region's vital grape and tomato harvests for Welch's and Red Wing stood in grave danger of rotting on the vines. The labor shortage threatened not only the economic foundation of the surrounding agricultural community but also critical food supplies during wartime rationing.

In an unprecedented decision that demonstrated both practical wisdom and civic duty, the college administration made the bold choice to suspend classes entirely, transforming the entire campus into a volunteer workforce. Students traded textbooks for harvest baskets, professors exchanged lecture halls for grape arbors, and staff members joined the effort to "save the harvest." This remarkable mobilization represented both an emergency response and a deep connection between Fredonia and its surrounding community that had been cultivated since the institution's founding.

The sight of college women, faculty members, and staff working side by side in the fields created lasting memories and strengthened bonds that would endure long after the war ended. Students gained firsthand understanding of the agricultural heritage that sustained their region, while local farmers experienced the college's genuine commitment to community welfare during the nation's darkest hour.

This extraordinary moment in Fredonia's history exemplified the institution's core values: service, community engagement, and the understanding that education extends far beyond the classroom. The "Save the Harvest" campaign of 1943 became a defining example of how higher education institutions can serve as vital community partners, stepping forward in times of crisis to preserve both economic stability and the spirit of mutual support that makes communities strong.

50 Years of Growth

to

to

The years following Fredonia’s designation as a founding member of the State University of New York in 1948 marked an extraordinary period of expansion. Over the next five decades, the college transformed from a small teacher-training institution into a full-fledged university, with most of the academic and residential buildings we see today rising across campus. New programs, new facilities, and new generations of students helped shape a vibrant academic community—one that thousands of alumni would come to know as home.

This era of growth paralleled monumental changes across the globe. In 1949, NATO was established, anchoring a postwar vision of international cooperation. Domestically, the 1964 Civil Rights Act signaled a turning point in the fight for social justice. Humanity reached farther than ever before when Pioneer 11 became the first spacecraft to explore Saturn in 1979. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 symbolized the end of the Cold War, and by 1994, new economic partnerships like NAFTA were reshaping trade and diplomacy across North America. Through it all, Fredonia remained a place where the values of learning, progress, and community thrived.

SUNY Status

The State University of New York, SUNY is created, and Fredonia becomes one of 11 colleges of education in the new state university system. This partnership opened doors to greater resources and opportunities while maintaining our distinctive character and close-knit community.

New York officially created the State University of New York on March 13, 1948, settling a longstanding question about the nature of higher education in the state. Thousands of returning veterans from World War II needed jobs and training, and the state could no longer confine higher ed to agricultural and technical programs, and teacher training colleges. Under the G.I. Bill of Rights, veterans were entitled to additional education with financial support from the federal government.

SUNY's First Radio Station: Seven Decades of Student Broadcasting Excellence

What began as a small radio club meeting on the third floor of Old Main in 1948 grew into a nationally acclaimed broadcasting powerhouse that earned recognition as the "Best College Radio Station in the Nation" in 2017. This remarkable journey reflects both Fredonia's commitment to hands-on student learning and the dedication of generations of student broadcasters who transformed a modest campus hobby into SUNY's oldest and most celebrated radio station.

The story started simply: students producing programs for broadcast on WDOE-AM in Dunkirk before establishing WCVF-AM on campus with an innovative system that used residence hall electrical systems to carry signals to any plugged-in radio. Originally housed under the Department of English and Drama, the station achieved full student control in 1966, embodying Fredonia's trust in student leadership and responsibility.

As the campus evolved, so did the station, moving through multiple locations—from Fenton Hall to Jewett Hall's basement, the Dods Hall gymnasium press box, and Gregory Hall—before finding its permanent home on McEwen Hall's second floor. The addition of WCVF-FM 88.9 in 1978 marked a new era, beginning with just 10 watts of power and eventually reaching 150 watts with a potential audience of 40,000 listeners across Northern Chautauqua County.

The formation of Fredonia Radio Systems, combining WCVF-FM and WDVL Cable 89.5, created a comprehensive broadcasting operation entirely student-run yet professionally executed. When FRS won the prestigious Abraham & Borst Award at the 2017 Intercollegiate Broadcasting System conference, defeating over 700 college stations nationwide, it validated what Fredonia had long known: that students given real responsibility, proper guidance, and institutional support can achieve excellence that rivals any professional operation.

Today, Fredonia Radio Systems continues this legacy of excellence, maintaining the same high standards of integrity and professionalism that earned national recognition while training new generations of student broadcasters in the art and responsibility of collegiate radio.

Fredonia's First Dormitory - Gregory Hall

Gregory Hall opened in 1951 as Fredonia’s first on-campus dormitory and student union, marking a major milestone in the development of a fully residential college experience. More than just a new building, it became the heart of a growing campus community.

The hall was named in honor of Dr. Leslie R. Gregory, the college’s former president, who led Fredonia through two of the most difficult chapters in its history—the Great Depression and World War II—when the college’s future often hung in the balance.

During a visit that same year to lay the cornerstone for the new administration building (later named Fenton Hall), Governor Thomas E. Dewey also participated in the dedication of the then-unnamed dormitory. In a spontaneous moment, he proposed naming it for President Gregory, acknowledging his unwavering advocacy for the college.

“Your president put the bite on me better, harder, and more successfully than anyone else,” Dewey said of Gregory’s lobbying efforts to gain funding for the much-needed dormitory. Not since the fire in 1900 had students lived in campus housing, often taking rooms in houses in the village.

Gregory Hall remains the only building on campus named for someone who was still living at the time of its dedication—a rare and lasting tribute to a president whose leadership ensured Fredonia' survival and shaped the college’s future.

First Wave of Campus Housing: Alumni, McGinnies, Cranston, Chautauqua, and Nixon Halls

–As Fredonia's student population surged in the postwar era, the need for on-campus housing grew rapidly. The college responded with a major residential expansion—building its first full group of dormitories in swift succession. This was the first of four waves of residence hall construction that helped transform Fredonia into a fully residential campus.

Alumni Hall – 1958

The second dormitory to open on campus, Alumni Hall was named to honor several distinguished graduates whose contributions helped establish Fredonia’s reputation for excellence:

- Fanny England Bartlett, 1882

- A.W. Dods, 1875

- Charlotte Putnam Landers, 1898

- James McGraw (East), 1884

- Carrie Livermore Record (West), 1898

It’s worth noting that the name Alumni Hall had previously been used for a women’s residence at 71 Central Avenue (now a bed and breakfast), which housed students from 1946 to 1958.

McGinnies Hall – 1960

The third residence hall on campus, McGinnies Hall stands out for its distinctive chevron-shaped design. It was named in honor of Joseph A. McGinnies, a longtime member of the Normal Board of Visitors and New York State Assemblyman from 1916 to 1935, recognizing his decades of service to both the college and the region.

Cranston Hall – 1961

Dedicated to Mary H. Cranston (Class of 1906), whose leadership on campus lasted for decades as Dean of Women from 1916 to 1949. In 2006, the building was transformed into the University Commons, now home to the University Bookstore, Convenience Store, Cranston Marche dining hall, and Starbucks. Today, Cranston serves upper-level students in a hall-style living arrangement.

Chautauqua Hall – 1962

Named in honor of Chautauqua County, Chautauqua Hall continues to serve as a corridor-style residence, primarily for first-year male students. It’s also home to a popular sand volleyball court, a favorite gathering spot during warm-weather months.

Nixon Hall – 1963

The last and smallest of the original corridor-style residence halls built during this first wave, Nixon Hall was named for Samuel Frederick Nixon. His service on the College Council from 1932 to 1952 paralleled the pivotal leadership of President Gregory, and he played an important role in helping guide Fredonia through a period of major transformation.

Designing the Future: I.M. Pei’s Vision Transforms the Fredonia Campus

–In a bold move that reflected Fredonia’s growing ambitions, President Oscar E. Lanford invited world-renowned architect I.M. Pei to design a modern master plan for the campus in 1962. The result was a transformational partnership that would define Fredonia’s look and feel for generations.

Working alongside longtime collaborator Henry N. Cobb, Pei envisioned a campus that not only supported academic excellence but inspired it through innovative design. Their plan dramatized Fredonia’s physical environment with six striking new buildings and a distinctive circular roadway—Ring Road—that still defines the campus layout today.

Pei's influence includes many of Fredonia’s most iconic structures: Maytum Hall, the Williams Center, Reed Library, Rockefeller Arts Center, McEwen Hall, and Houghton Hall. Their design for Reed Library earned national acclaim, winning the 1969 Prestressed Concrete Institute Award.

In 1972, the duo returned to design Erie Dining Hall and the surrounding suite-style residence halls, expanding their architectural vision into student life.

This collaboration between a rising public college and one of the 20th century’s most influential architects signaled Fredonia’s commitment to world-class learning and design. Pei's campus plan wasn't just a construction project—it was a statement of purpose, a modern blueprint for a university with its eyes on the future.

1966-1976: A Decade of Dynamic Growth

–Following the transformative vision set forth by the Heald Report and New York's ambitious university master plan, Fredonia embarked on an extraordinary journey of growth and innovation that would redefine higher education in our region.

Unprecedented Growth by the Numbers

The statistics tell a remarkable story: enrollment surged from 1,368 students in 1961 to 3,226 by 1968—nearly doubling in just seven years. This explosive growth represented a dramatic turnaround from the lean war years when Fredonia had just 64 graduates in 1945, expanding to an impressive 414 graduates in 1968. Likewise, the teaching faculty grew from 75 in 1945 to 241 by 1968, ensuring excellence kept pace with expansion.

Expanding Physical Foundations

To accommodate this unprecedented growth, Fredonia boldly expanded its footprint. In 1964, the college acquired 125 acres on the northeast side of Temple Street, followed by another 70 acres west of Brigham Road in 1967. This visionary land acquisition set the stage for our modern campus design, anchored by I.M. Pei's iconic architectural legacy: Maytum Hall, the Michael C. Rockefeller Arts Center, Reed Library, and McEwen Hall—striking landmarks that continue to inspire learning and creativity today.

The campus also welcomed the Kirkland (1967) and Andrews (1970) residential complexes, creating vibrant communities that could house thousands of new students while fostering lifelong connections and collaborative learning experiences.

Academic Excellence Redefined

This era witnessed a revolutionary transformation in academic structure and philosophy. Traditional broad departments evolved into specialized disciplines: the Science Department separated into Biology, Physics, Chemistry, and Geology, while the Social Studies Department divided into History, Political Science, Sociology, and Economics. This specialization represents just a few of the changes that allowed for deeper expertise and cutting-edge research.

Perhaps most significantly, faculty were encouraged to strengthen themselves professionally through research and publications—practices commonplace today but revolutionary for the era. Gone were the days of strict uniformity that constrained the old normal schools. Fredonia emerged as among the first institutions in New York to embrace the autonomy and promise of fully-realized liberal arts education.

The foundation built during these pivotal years continues to propel Fredonia toward an even brighter future.

Maytum Hall - A Legacy of Leadership and Vision

–In 1968, Fredonia unveiled its striking eight-story, semi-circular administration building, honoring it with the name Maytum Hall—a tribute to Arthur R. Maytum, whose remarkable life paralleled the college's own journey from humble beginnings to greatness.

Born in nearby Dunkirk in 1866, just one year before Fredonia Normal School's founding in 1867, Maytum embodied the spirit of regional leadership and innovation that would define our institution. His entrepreneurial vision led him to organize the Dunkirk-Fredonia Telephone Company, connecting communities through groundbreaking communication technology that transformed the region.

Maytum's dedication to public service was equally impressive. He served as president of the Fredonia Village Board during pivotal years (1910-1911, 1925-1926) and as Supervisor of the Town of Pomfret from 1931 to 1938. His commitment extended beyond government to active membership in the Masons, Odd Fellows, and Rotary, where he championed community values and civic engagement.

Most significantly for Fredonia, Maytum devoted 26 years (1927-1953) to service on the College Council, providing steadfast guidance during crucial periods of institutional growth. His unwavering commitment to educational excellence helped shape Fredonia's evolution into the comprehensive institution we know today.

The naming of Maytum Hall in 1968 recognized not just his extraordinary service, but the leadership example he set for future generations. This legacy continues to inspire: in 1984, the Maytum family and Dunkirk-Fredonia Telephone Company established a scholarship in his honor, supporting Communications/Media and Computer Science students from Chautauqua County—ensuring that Arthur Maytum's vision of connecting communities through innovation lives on in each new generation of Fredonia graduates.

Giving to the Arthur R. Maytum Scholarship supports an award based on merit and need with preference to student from Northern Chautauqua County.

Kirkland Hall Complex

Following the successful construction of corridor-style residence halls from 1958 to 1963, Fredonia entered a new era in student housing. The second wave of construction introduced suite-style living—an innovative design in which small clusters of student rooms (typically housing 2–4 students each) are connected by a shared common area, often including kitchen and bathroom facilities.

This new layout marked a shift in how students lived and built community on campus. While corridor-style housing remains effective in fostering hallway-based friendships, suite-style living offers a more intimate setting for collaboration, independence, and shared responsibility. Research has shown that students thrive socially in both environments—but suite-style housing added new possibilities for creating tight-knit living communities.

In 1967, Fredonia unveiled the Kirkland Complex, a suite-style residential area that redefined campus living. Each hall was named to honor influential figures in American history and on campus:

Disney Hall – Named for Walt Disney, the visionary entertainer and entrepreneur, and primarily housing upper class students.

Eisenhower Hall – Named for Dwight D. Eisenhower, the 34th President of the United States and WWII Allied Commander, also serving upper class students.

Grissom Hall – Named for astronaut Virgil "Gus" Grissom, one of NASA’s original Mercury Seven and the first person to fly into space twice.

Kasling Hall – Named for Dr. Robert Kasling, a beloved Geography professor whose career at Fredonia spanned from 1946 to 1966.

Alongside these residence halls, the complex introduced the Erie Dining Hall, a modern and flexible dining facility that quickly became a central gathering place for students living across campus.

The Williams Center - Building Community, Honoring Leadership

On a remarkably mild November afternoon in 1968, with temperatures approaching 50 degrees and intermittent light rain blessing the ceremony, the sounds of Rudolph Emilson's marching band filled the air as Fredonia broke ground on what would become the crossroads of campus activity. The ambitious Campus Union Center project promised to transform student experience with a bold architectural vision that matched the college's aspirations.

I.M. Pei's Vision

The plan was bold: a magnificent 95,000-square-foot, two-story oval building designed by the legendary I.M. Pei, set to open in 1970. This $3.9 million construction of pre-stressed concrete would house an 800-seat multipurpose social hall and a 400-seat cafeteria, along with conveniences of the era including barber and beauty shops. A connecting "spine" would link the new Union to Reed Library, creating an integrated hub for academic and social life where generations of students would gather, learn, and grow.

A Leader's Dedication

In that same year of 1968, H. Kirk Williams—distinguished community leader, successful businessman, and generous philanthropist—was named Chairman of the College Council, beginning an extraordinary chapter of service that would span decades. Appointed to the College Council in 1965 by Governor Nelson Rockefeller, Williams embodied the kind of steadfast leadership that transforms institutions.

For nearly three decades, Williams became a beloved fixture at every commencement ceremony, personally congratulating thousands of graduates with a warm handshake in their moment of triumph. This simple gesture—repeated year after year, graduate after graduate—symbolized his deep personal investment in each student's success and his unwavering commitment to Fredonia's mission.

Legacy of Generosity and Vision

Williams and his wife's significant contributions to the college's capital campaign helped raise $5 million and established Fredonia's first endowed professorship—the Williams Visiting Professorship—bringing distinguished scholars and innovative ideas to campus. Their philanthropy created lasting opportunities for academic excellence that continue to enrich the Fredonia experience.

In 1996, in recognition of his decades of extraordinary service and transformative leadership, the Campus Union Center was renamed the Williams Center. This honor reflected not just his financial contributions, but his embodiment of the community spirit and personal dedication that the building itself was designed to foster—a place where students, faculty, and staff come together as one Fredonia family.

Today, the Williams Center remains the vibrant social and cultural heart of campus, a testament to both architectural vision and the power of individual commitment to strengthen our shared community.

Reed Library: I. M. Pei's Architectural Legacy Anchors Academic Excellence

When Reed Library opened in 1969, it brought world-class architectural distinction to Fredonia's campus through the striking design of Pei Cobb Associates, featuring the unmistakable modernist vision that would become synonymous with I. M. Pei's legendary career. This bold concrete and glass structure, with its dramatic geometric forms and innovative use of space and light, remains one of the most impressive examples of Pei's institutional architecture, continuing to captivate visitors and students more than five decades later.

The building's revolutionary design represented a departure from traditional collegiate architecture, embracing the clean lines and functional beauty that characterized the modernist movement. Pei's masterful integration of form and function created spaces that were both visually stunning and supremely practical for academic work.

Named in honor of former United States Congressman Daniel A. Reed of Sheridan, the library was conceived as both a repository for books and a comprehensive center for learning and academic support. The building's innovative design maximized functionality while creating inspiring spaces for study and research, with the main floor alone spanning an area larger than a football field.

From its opening, Reed Library established itself as far more than a traditional library, housing multiple academic support services that recognized the evolving needs of modern higher education. The facility's 800 seats were strategically distributed across various environments, from quiet individual study areas to collaborative spaces, accommodating different learning styles and academic pursuits.

The 1991 completion of the Carnahan-Jackson Center addition, designed by Pasanella + Klein Associates, dramatically expanded the facility's capacity and services, demonstrating Fredonia's ongoing commitment to academic excellence and student success.

This thoughtful expansion complemented Pei's original vision while adding crucial space for specialized services including Tutoring Services, Academic Advising, Disability Support Services, and the Professional Development Center. The addition seamlessly integrated with the original structure, creating a unified complex that could serve the growing and diversifying needs of the campus community.

Today, Reed Library stands as both an architectural landmark and the beating heart of academic life at Fredonia. Operating 82 hours per week with 40+ computers and robust wireless connectivity throughout, the facility serves as a technological hub where traditional scholarship meets digital innovation. The library's remarkable specialized collections—from Austrian author Stefan Zweig's papers to world-renowned saxophonist Sigurd Raschèr's archives, plus unique holdings on the Holland Land Company and local Western New York history—reflect Fredonia's commitment to preserving cultural treasures.

The library's impact extends far beyond its physical walls, with monthly statistics revealing its central role in campus life: 24,000 webpage visits, 6,000 article searches, and 2,000 items circulated, including international engagement from 88 countries. Housing over 200,000 volumes with access to 20 million more across SUNY, Reed Library welcomes 500,000 in-person visits annually, with its Library Instruction program reaching 4,000 students each year.

This enduring success represents the fulfillment of Pei's architectural vision and Fredonia's educational mission, creating a space where cutting-edge research, collaborative learning, and individual study flourish within one of the most architecturally significant buildings in the SUNY system.

Andrews Hall Complex

As Fredonia’s enrollment continued to grow in the 1970s, the need for additional student housing sparked the next phase of campus expansion. The result was the creation of the Andrews Hall Complex, a suite-style residential area located just beyond the Kirkland Complex. Designed to meet the college’s long-term housing needs, these modern living spaces further strengthened Fredonia’s identity as a vibrant residential campus.

The complex was named in honor of Florence Maud Andrews, a distinguished graduate of the Fredonia Normal School’s Class of 1889 and a beloved teacher in the Dunkirk schools for many years. Her name stands as a tribute to Fredonia’s enduring legacy of educational excellence.

Within the Andrews Complex are four residence halls—each named by popular vote of the student body, making this one of the few places on campus where student voices were directly reflected in the naming process:

Schulz Hall – Named for Peanuts creator and cartoonist Charles Schulz, whose humor and heart had a lasting impact on American culture.

Igoe Hall – Named in memory of James Robert Igoe, a former Fredonia student whose life was tragically cut short in a drowning accident on Lake Erie.

Hemingway Hall – Named for legendary American novelist and journalist Ernest Hemingway, whose bold style and adventurous life continue to inspire.

Hendrix Hall – Named for groundbreaking guitarist Jimi Hendrix, whose creativity and innovation defined a generation of music.

With its strong sense of community, personal connection, and student participation, the Andrews Complex capped off a transformative era in Fredonia’s residential life—setting the stage for decades of connection, collaboration, and campus spirit.

"Words": How William King's Tin Men Created Three Man Hill

In the mid-1970s, acclaimed sculptor William King transformed a modest rise on Fredonia's campus into one of its most beloved landmarks with his installation of three distinctive metal figures. The sculpture, officially titled "Words" but affectionately known as "The Tin Men," sits strategically positioned between the wood lot and Rockefeller Arts Center, overlooking Dods Hall, the soccer fields, and Symphony Circle.

King, born in Jacksonville, Florida in 1925, had established himself as a master of figurative sculpture whose work graced prestigious institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. After studying at Cooper Union, where he began selling sculptures before graduation, King developed his signature style of figures with disproportionate body parts and expressive character poses that gently mocked human nature.

The three metal figures he created for Fredonia exemplified this approach, standing as silent sentinels that quickly captured the campus imagination. Students began referring to the location simply as "Three Man Hill," a name that has endured for nearly five decades and become as integral to campus geography as any official building designation.

The sculptures have served multiple roles in campus life, functioning as a gathering place for classes, a quiet retreat for contemplation, and a popular spot for watching sunsets over the Western New York landscape. Students have used the hill for everything from sledding in winter to photographing star trails on clear nights, while others find solace leaning against the sculptures during stressful times.

Theatre arts students recall outdoor classes beneath the watchful gaze of the tin men, while photography students discovered the perfect vantage point for capturing the interplay of art, nature, and architecture. The hill's elevated position provides sweeping views that have made it a natural destination for those seeking both inspiration and respiration from the demands of academic life.

King continued creating art until just days before his death in March 2015, but his legacy at Fredonia remains vibrantly alive through these three figures that have watched over generations of students. "Words" represents more than public art—it embodies the way creative expression can transform a simple geographic feature into a cherished community landmark, connecting students to the natural beauty of their campus.

Building for a Bright Future

to

to

This quarter-century unfolded against a backdrop of profound national transformation. The tragic events of September 11, 2001, tested the country's resilience and unity, while the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 opened new frontiers in medicine and science. The 2008 election of Barack Obama as the nation's first African American president marked a historic milestone in the ongoing pursuit of equality. Technological breakthroughs revolutionized how we communicate and learn—from the introduction of smartphones to the rapid development of social media platforms that connected communities across the globe. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, it challenged institutions everywhere to innovate rapidly, leading to new models of education and scientific collaboration that produced life-saving vaccines in record time.

The dawn of the new millennium found Fredonia poised to embrace unprecedented change and innovation with the next 25 years witnessing remarkable technological transformation, evolving pedagogies, and an increasingly diverse and globally connected student body. Through periods of both challenge and opportunity, Fredonia remained steadfast in its commitment to academic excellence, creative expression, and community engagement—adapting to meet new challenges while preserving the core values that have defined the institution for two centuries.

Clock Tower

The Lake Shore Savings Clock Tower and Carillon are dedicated, and the Natatorium is completed. These additions enhanced both our campus beauty and our recreational facilities, enriching the student experience.

Juliet J. Rosch Recital Hall

What began as a practical renovation project for Mason Hall's aging facilities transformed into something extraordinary—a world-class performance venue that would elevate Fredonia's music program to new heights of excellence.

From Necessity to Innovation

By the late 1990s, the need to upgrade Mason Hall and the intimate Diers Recital Hall had become critical. Initial plans called for simple renovations and modernization of teaching and practice spaces. However, through advocacy from a bipartisan group of assembly members and favorable changes to state guidelines, the vision expanded dramatically. The result was an ambitious plan to construct a stunning new 500-seat recital hall—twice the size of Diers, yet more intimate than the 1,200-seat King Concert Hall—creating the perfect venue for showcasing musical artistry.

Architectural Excellence Meets Acoustic Perfection

The Rosch Recital Hall became the cornerstone of a transformed Mason Hall, now a magnificent 100,000-square-foot facility comprising three interconnected buildings that unite campus musicians under one roof. Designed by renowned architect J. Arvid Klein of New York City's Pasanella + Klein Stoltzman + Berg Architects, every detail was crafted with precision over 148 weeks of construction requiring more than 70,000 hours of skilled labor.

The hall's breathtaking interior features Oregon forest hardwood flooring laid with intricate end-groove and tongue-in-groove techniques, while three levels of audience seating surround a performance stage. Most remarkably, 1,400 custom acoustical panels line the walls, creating sound quality unmatched in most halls of its size—transforming every performance into an intimate, transcendent experience.

Recognition and Legacy

In 2005, the Rosch Recital Hall earned international acclaim as one of only five buildings worldwide to win awards from the International Interior Design Association, chosen from hundreds of global projects for "the clarity of their ideas, and the ability of the designer to develop that concept through details in a clear and consistent way."

Honoring a Life of Service

The hall's name honors Juliet J. Rosch, Class of 1930, whose extraordinary legacy embodies Fredonia's finest values. As a dedicated teacher in the Falconer School District during the Great Depression, Mrs. Rosch recognized that students needed comfort as well as learning. Her remarkable ability to see the best in others and help them reach their potential defined her career and continued through her establishment of the Juliet Anderson Rosch Scholarship Fund—a permanent endowment supporting educational aspirations at Falconer Central School.

Mrs. Rosch's devotion to her alma mater culminated in a $1 million gift—the largest in Fredonia's history at the time—that made this world-class facility possible. Beyond her educational philanthropy, she served over 20 years on the board and as treasurer of Lutheran Social Services, was active on the WCA Hospital Board of Directors, and remained deeply involved in the First Covenant Church. In 2000, the Fredonia College Foundation honored her with its Distinguished Service Award.

Today, the Rosch Recital Hall stands as both a testament to architectural innovation and a living memorial to the power of education to transform lives—where every note played honors the vision of a teacher who believed in helping others reach their potential.

Giving to the Juliet J. Rosch Endowment for the School of Music supports priority needs of the School of Music and scholarships.

Cranston Hall to University Commons: Building Community

The University Commons transformed campus life when it opened in 2006, creating a vibrant modern hub where students gather, dine, and connect daily. This four-story addition to the historic Cranston Hall brought together dining, shopping, and residential spaces under one roof, becoming the heart of our Fredonia community.

Cranston Hall had served as campus's social center since 1961, hosting millions of meals alongside meetings, banquets, and dances in a facility named for Mary Cranston, the beloved Dean of Women from 1928 to 1949. By the late 1990s, President Hefner and others recognized the need for expansion to better serve the growing campus community.

The ambitious project took shape through an innovative partnership between the Fredonia Faculty Student Association, the Office of Residence Life, and the State University of New York Construction Fund, with crucial support from local legislators in Albany. Ground broke in 2004, marking the first new student housing addition since the Andrews Hall Complex in 1970.

Today, the University Commons houses more than 120 students while serving the entire campus through the renowned Cranston Marche dining center—a marketplace-style facility widely regarded as one of "the best restaurants in Chautauqua County." The building's convenience store, bookstore, and Starbucks create a bustling atmosphere where most students pass through daily, fostering the community connections and campus traditions that make Fredonia special.

Science Center Ushers in a New Era for STEM

Long known for its excellence in teacher preparation and nationally recognized Music program, SUNY Fredonia made a powerful statement about its commitment to the sciences with the opening of the new Science Center in 2014. This four-story, 92,000-square-foot facility marked one of the most ambitious construction projects in the college’s history—ushering in a new era of innovation, discovery, and interdisciplinary learning.

With a ceremonial "splicing" of a giant double-helix DNA strand, the campus celebrated the building's opening and its symbolic role in shaping the future of science education at Fredonia. Connected to the existing Houghton Hall and constructed over three years, the Science Center became a long-awaited hub for students and faculty alike.

Inside, the facility houses 16 state-of-the-art research labs, 10 teaching labs, computer labs, classrooms, a 120-seat auditorium, a greenhouse, an observatory, and even a café at the heart of its glass-walled lobby—inviting collaboration and conversation. One of its most striking design features is the transparency of its interiors: labs and classrooms with glass walls open toward interior corridors, reflecting the Center’s mission to foster visibility, connection, and interdisciplinary thinking.

Built to support the growing number of students in Biology, Chemistry, Biochemistry, Molecular Genetics, Environmental Science, Medical Technology, Exercise Science, and Science Education, the Science Center stands as a testament to Fredonia’s expanding academic mission.

This bold investment reinforced Fredonia’s dedication not just to tradition, but to the future—where curiosity, research, and innovation lead the way.

A New Era for the Arts: Expanding the Rockefeller Arts Center

More than 40 years after the iconic Michael C. Rockefeller Arts Center opened its doors, Fredonia took a major step forward in supporting the creative energy of its campus. In October 2016, the university unveiled a striking 40,000-square-foot addition—an expansion designed not just to grow the space, but to transform how the arts thrive at Fredonia.

The two-story addition, extending along the west side of the original I.M. Pei-designed structure, was carefully crafted to echo Pei’s bold architectural vision while addressing the evolving needs of modern artists. Pei’s legacy lives on—he designed five landmark buildings at Fredonia—but this addition marked a new chapter of innovation and collaboration.

Designed with students in mind, the space is in near-constant use. On any given day, it buzzes with creative energy: students welding, throwing clay, rehearsing stage combat, or choreographing movement across studios filled with natural light. The building’s openness fosters spontaneous interaction—something that was long missing.

As Ralph Blasting, then-dean of the College of Visual and Performing Arts, put it: “Yes, students will have better studios and equipment. But more importantly, visual artists, actors, dancers, designers, and musicians will literally be crossing paths in the building, mirroring the crossing of disciplines which now defines the arts industry.”

With this dynamic expansion, Fredonia reaffirmed its commitment to the arts and to the kind of interdisciplinary learning that powers creative careers. The Rockefeller Arts Center is no longer just a building—it’s a hub of inspiration and a catalyst for the future.

Farewell to the Spine: Honoring a Campus Icon

Since 1968, the Academic Spine Bridge—known simply as The Spine—was more than just a walkway. Designed by renowned architect I.M. Pei, the 460-foot bridge connecting McEwen Hall and the Williams Center embodied the modernist vision that defined Fredonia’s campus. With its striking lines, tucked-away alcoves, and elevated views of campus life, the Spine became a beloved part of the Fredonia experience for generations of students.

But over time, the bridge’s original purpose faded. In 1991, when Reed Library’s entrance was relocated to the ground floor and the Spine entry closed, its function as a primary pedestrian route diminished. By 2016, the structure—composed of over 1,300 tons of reinforced concrete, roughly the weight of three jumbo jets—had deteriorated significantly and no longer met modern safety codes.

Despite deep affection and nostalgia, students and alumni understood that safety had to come first. With replacement costs projected at $3–4 million and substantial code compliance challenges, preserving the original bridge wasn’t feasible. Still, its removal marked the end of an era.

Alumni continue to recall the Spine with fondness—its quiet corners, its panoramic views, its role as a symbolic link across campus. While the physical structure is gone, its memory lives on in stories, photos, and the shared sense of place it helped create. In the spirit of sustainability, much of the concrete and steel from the bridge was recycled, helping reduce costs and environmental impact.

The Spine may no longer stretch above the Fredonia campus, but its legacy remains firmly rooted in the hearts of those who crossed it.